Nepal, Part 2: On the Ground and off the Grid with dZi

Mountainfilm Festival Director David Holbrooke just spent two weeks in Nepal with dZi Foundation, our new nonprofit partner, which works with some of the most remote villages in Nepal to improve quality of life and reduce poverty and disease. This is the second of two blogs. Read "Nepal, Part 1: 40 Hours to Kathmandu."

We were in the small eastern Nepal village of Nimchola, which is only accessible by foot, when an elder asked if dZi would help build a community center to bring the villagers closer together. Ben Ayers, the country director for dZi, translated the request to our group of English speakers and said, “This is somewhat awkward because it isn’t really what we do.”

Finding out what dZi does in these remote regions is the reason I was in this remote village in Nepal. Recently, the dZi Foundation became Mountainfilm’s first nonprofit partner. This innovative relationship was proposed by the organization’s founder, Ridgway, Colorado, resident Jim Nowak, who wanted me to see firsthand the impact of the work being done by his team.

So here I was with Jim and Ben from dZi; Eric Ming, who is writing an article about the trip for the Telluride Watch; Kevin Fritz, whose father Tom Fritz is the head of marketing at Marmot, a big supporter of dZi; and my wife, Sarah Holbrooke, executive director of The Pinhead Institute. Also with us was a guide named Abi and four porters who were half my size, yet incredibly strong and surefooted.

There are no roads in the regions where dZi works, so we helicoptered out of Kathmandu, flying over terraced fields and catching a glimpse of Mount Everest to the north. We flew for only 45 minutes, but the incessant movement of Kathmandu seemed a world away when we landed in Rakkha, a small but growing village of friendly farmers.

The farmers proudly showed us their crops, an array of potatoes, rice, broccoli, cardamom (a big cash crop) and many other plantings. This kind of crop diversity wasn’t possible until dZi funded and helped build a water project in Rakkha that dramatically changed the state of farming as well as public health. Mothers repeatedly told us their kids are healthier, stronger and sick less often because they now eat better.

I asked them what other impact dZi has had on their lives, and they told me the foundation has helped them bond as a community in new ways. For instance, the only way the water project could succeed was if they cooperated and collaborated on such issues as land use, construction and transparent fund allocation. As they said, “Unity matters in a way that it didn’t before.” One mother told us that women have assumed a new role because they are involved in financial decisions now. I asked the men how they feel about this development, and there was much laughter but, apparently, no resentment.

Aside from water projects, dZi is shifting how people in these small, rural villages deal with human waste. One traditional option entails people squatting over a pit with pigs living beneath the rickety restroom. Efficient for sure, but when those same pigs are eaten (as Homer Simpson said, “Oh, Mr. Pig. It’s not your fault you’re so delicious.”), people often get tapeworms. The most traditional way for rural Nepalis to do their business, however, is to just squat and crap pretty much anywhere, so dZi is convincing people to change a routine that dates back centuries.

The process involves helping villagers convert to a dedicated toilet where urine is collected in a vat and used as fertilizer, and excrement stays in a local-style septic tank fortified by impressive rock walls. We walked through approximately a dozen villages where this new system was being integrated or already in place. There is universal acceptance that the transition is improving health, and studies back it up, showing a 50-percent cut in diarrheal disease in dZi areas. Creating “open defecation-free zones” isn’t glamorous work, but it’s making an enormous difference in the everyday lives of these Nepalis.

dZi’s operations impact nearly 30,000 people over roughly 300 square miles on the eastern side of Nepal, incredibly far from the country’s tourism activity. Forty thousand Westerners trek in the Everest region, bringing enormous revenue to that area. Over the eight days of our journey, we saw only four videsi (foreigners), all scruffy young men in the town of Gudel, which is on a lightly traveled trekking route. In most of the many villages we walked through, we were the first white people these folk had seen since the last time dZi was there. At 6 foot 6 inches, I was of particular interest, especially to the children whose welcome involved festooning me enthusiastically with rhododendron garlands and silk khatas.

Even though these people live at a much lower altitude than their countrymen to the north, they still reside in steep mountains, so it’s like hiking Jud Wiebe all the time, except with the occasional water buffalo on the trail. It was incredibly scenic as we wound our way up into rhododendron forests and down through shepherd’s meadows, often coming to a river with bamboo bridges. We topped out at 11,400 feet, but we could see peaks in the distance that were twice as high. Our Sherpa guide Abi also works in those big mountains and said the route we walked is as beautiful as anywhere he’s been in the country. He hopes to establish a trekking route here that would be an economic boost to this undiscovered region.

In the meantime, dZi faces a real conundrum in a town such as Rakkha. It has helped build toilets, installed irrigation systems and taught organic and pesticide-free farming methods. The quality of life for these villagers is better, but children still go to schools that are dark, dirty and dangerous (particularly if Nepal suffers the major earthquake that’s widely expected, part of an 80-year cycle with the last one in 1934; Kathmandu is considered one of the most earthquake-exposed cities in the world).

These Nepalis have tremendous needs, but dZi’s resources are limited, which forces it to perform a version of development triage, figuring out what these people need and want and assessing whether or not dZi is the right organization to make it happen. And if it’s not, there aren’t many other options for assistance: Every time we met with these small communities, we were told dZi is the only outside aid group working in their village. These places are too tiny for USAID, the big NGOs (such as the Gates Foundation) or even the Nepali government, so the work is left to the dZi Foundation to do what it does incredibly well — simply showing up in these isolated areas.

It puts a lot of pressure on this small organization, but the team seems up to the task with dedicated Americans working in conjunction with a strong Nepali staff, many of whom were educated in the U.S. and have returned to Nepal to improve the lives of their people.

It’s a good thing that the people of the dZi are so committed because there’s an enormous amount of need in this region. And it’s tricky to navigate, which is why the elder in Nimchola won’t get his wish for a community center funded — at least not by dZi because it aims to help the people of this region get healthier, thereby empowering the villagers themselves to build a community center.

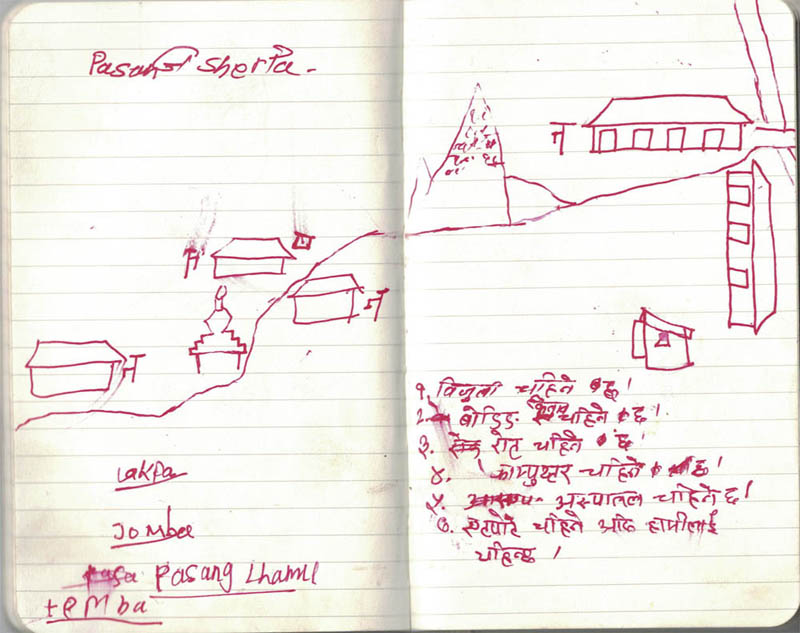

I asked the kids of Nimchola what they see for the future of their town. They were too shy to say anything in front of us, but when we asked them to take my notebook and draw a vision of their village, they returned a hopeful sketch that incorporated electricity, a hospital and even a road. Their dreams are still on the drawing board, but dZi does introduces the community to the skills, confidence and improved health to move beyond the baseline and build the future you see below.